vague terrain

Artist Statement

vague terrain

The French term terrain vague is used by architects and urban planners to describe forgotten spaces which are left behind as a result of post-industrial urbanization. Interestingly, the term embodies two contrasting viewpoints: the first looks at these spaces negatively as representing disorder and disintegration; the second highlights their positive potential as free spaces in an urban environment that is becoming increasingly specialized. The ideas encompassed in terrain vague serve as a conceptual model for my work.

What interests me as an artist is being able to create photographically this sense of “free” space, using as a starting point, subject matter from forgotten or other marginalized aspects of the built environment. I do this by searching for environments that are in transition, under construction or demolition, or built to be temporary. I have most recently been drawn to garden trade show environments while they are undergoing construction and demolition. I attempt to strip away obvious references to function and purpose and, instead, emphasize each scene’s sculptural and display characteristics. In this way, these spaces are freed from their initial and sometimes negative contexts (disorder, abandonment, overt commercialism, tackiness), and instead suggest a kind of alternate order created through the photograph.

Catalogue Critical Essay for Lisa Stinner’s Platform Gallery Exhibition, Vague Terrain Home and Garden Show and Tell

By Trevor Boddy

Nestled within cities are other, more provisional cities. A mere fragment of a city stumbled onto at a temporary trade fair can be used to re-constitute the entire metropolis—a mere portion, fractal-like, possessing the code for the urban whole. Nestled within the seemingly blank surfaces of images are to be found other, more provisional images. Just as fractal-like, the ghosts, the patterns, the vaprous residue of activities past can impute a whole lived moment. The implication of the whole proceeds from a tiny piece; information from the conditional implies the universal; a leftover reconceived becomes the entire banquet—such is the place of photography in the new century.

Ideas like these are at the core of Lisa Stinner’s exhibition Vague Terrain. Her large Chromeria print colour photographs of un-peopled environments possess a kind of Barthesian equipoise, being equally about and not-about their obvious visual subjects. Yes, those are pix of ‘home and garden’ shows somewhere at some state of creation or dissolution. And they are much more. Yes, she excavates ordinary Modern architecture wherever she visits, emptying the Utopian ambitions out of it by exaggerating its patina of occupation. And there is more to it than that. Let’s see this clearer by talking around and into her images themselves.

Camping at the Sportex

First, a story: in the mid-1960s I went as a kid with my dad to Edmonton’s rite of spring, the annual Home and Garden Show at the Sportex. Under the harsh trade hall light, with the slight smell of shit lingering from the Charolais Show swept out only days before, kitchen sinks, cabinets, garden sheds, food processors, chaise longues and closet organizers became capitalized, highlighted, rendered in quotes. The intensity of the smell and the light that night seemed to call forth in me a removal into a thought-framed, second-order reading of the show.

I later came to know this special attention as the quotes of ironic camp—no longer was this just the home and garden show, but was fore-grounded to become instead “The Home and Garden Show.” This all came clearer a few years later, when I read Susan Sontag’s famous essay, “Notes on Camp,” written about the same time, and published in her 1966 collection Against Interpretation, where she defines camp as “seeing the world in quotation marks.” Wandering the aisles of displays with my insipient Beatle cut, I thought it was just me who saw my own suburban domesticity strange-made in these temporary displays of kitchen counters and rock gardens. But dad got it, too, and he spent more of the evening laughing at things with me than considering their actual purchase for our West Edmonton bungalow.

I have another memory of that night, fused with the first. Topped-up with orangeade and my ritual bag of Old Dutch chips, we walked back to the car. On the way through the surging March night I saw my first racial incident—drunk cowboys taunting CN porter’s sons, boiling into a fist fight. Fear from this disturbing clash fused with the artificiality of the exhibition, the domesticity of childhood strange-made with the adult realm of social competition, the appearance of environments interchanged with the appearance of people. I may have become an architect that night. I certainly became an architecture critic.

These memories flooded out while gazing at Lisa Stinner’s photographic investigations of home and garden shows in Canada, the United States and Europe. One of the ironies of the works shown at Platform Gallery are her choice of titles for her photographs, giving only the city where the shot was taken (why not the venue, or the date, or the event?), as if that information might be important to their understanding, as it is in street photography. But these events are nearly identical town-to-town, making this place- naming almost completely beside-the-point. This, of course, is Stinner’s point.

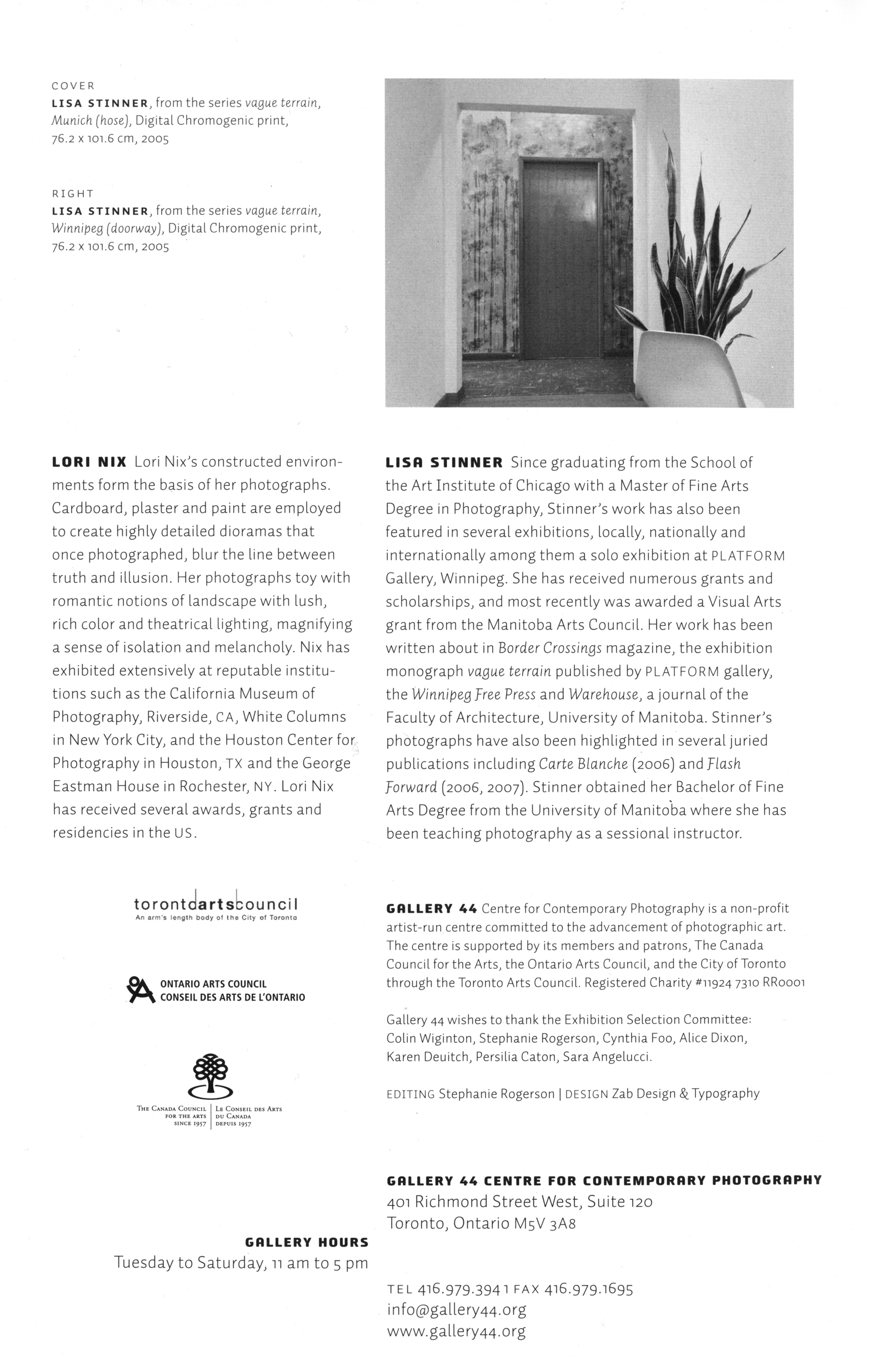

The second half of Stinner’s titles, in parentheses, are not a true naming or declension of meaning for the image, but rather the name of one object in the field of view—(rock), (pole), (plant), (coil), (microphone), (doorway), (hose), (rope), (generator), (concrete). Several sub-titles are made more specific by the addition of a word—(cherry tree), (poppy mound), (black wall)—but these are just as emptied of meaning. Putting her titles together, the place, named, does not matter, and the foreground subject, named, is banally evident. Place and subject, those bugbears of photography, have now been filed away by her titles, so the more important business of Stinner’s image-intentions can begin.

The home and garden shows that are her recurring subject are by definition provisional, packed up into tractor trailers, hauled away on Sunday nights to the next convention centre or sports palace, and then re-planted and re-built by Thursday evening for the eyes of another town. These landscapes on the make are evident in the photograph Chicago (tree), which shows a long-needled pine tree just in from the nursery stuck in a new pile of sand, the concrete blocks that will edge the display still loaded on pallets beside it. A similar pre-exhibition palette is found in Toronto (white sand), where a snowbank of shiny silicate and rows of potted shrubs are literally backed into the corner of some convention hall.

By capturing the moment of their assembly, Stinner reveals the home and garden show as the paradigm of the consumable consumer environment. This is doubtless the reason this quietly subversive photographer travels the world to shoot them. For Stinner, the brief efflorescence of the home and garden show becomes an analogue for the time-capturing of photography itself.

Modern Elisions

Only two of the images in the exhibition give architectural evidence of the urban locations named in their titles, both from Montreal. Montreal (concrete) has its background framed by one of that city’s waterfront concrete grain terminals. This immense industrial building— with others in Montreal and Calgary — were celebrated by Le Corbusier in his 1923 Towards A New Architecture as the “first fruits” of the new era of modernism, evidence of what he called the “engineer’s aesthetic.”

The engineering of Stinner’s own aesthetic is evident in another new planting captured in Montreal (screen), where a frosted glass screen frames a grouping of perennials on one side, but perhaps not the other. What seems to be second glass screen perpendicular to the first seems to me a digital insertion into the on-site photograph. Clues to this are in the perspective of the greystone 19th century religious building reflected there not aligning with the rest of the image, plus this supposed second glass screen lacking the black steel frame of the larger one to its left. Whether a found reflection or digital insertion, the neo- classical architecture acts as a counter-foil to the willed greenery of the planted shrubs, a contrasting reminder of how short a time they have been growing there, in the same way the stolid grain silo concrete makes the new plantings in the other Montreal image seem more ephemeral. In Toronto (black wall), Stinner digitally manipulates colour to pull back the saturation of the green of the plants, their chlorophyll seemingly replaced with ashes.

The tropes of architectural modernism are also evident in Munich (hose), where one of Europe’s surprisingly sophisticated constructions for a temporary garden show is composed and shot to recall Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. This, or perhaps it refers to Jeff Wall’s re-shooting of that icon of the heroic 1920s with the cleaning lady present: Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona. As with most of Stinner’s parenthetically (sub-titled) named subjects, the coiled yellow hose here is a stand-in for human agency and figural presence, the scene viewed again as if Wall’s elaborately-posed cleaning lady had just gone out for coffee. In Wall’s photograph, the cleaning lady also stands for Lily Reich, Mies’ lover and collaborator who shaped the pavilion design and interior appointments more than he did, but whose contributions the architect spent the second half of his life suppressing.

Like the Vancouver School, Stinner is interested in the intersection of vestigial landscape with consumerist development, and in the incidental eruption of the banal and the offhand. She rejects, however, the artifice, the sometimes fey referentiality, the staged or found spectacle of Wall, Roy Arden, Christos Dikeakos and others. A second image from the same German city, Munich (rope), is an image carefully composed to recall the same Mies pavilion, with differently-textured stucco walls recalling the opposed dark green marble and golden onyx at Barcelona. These walls frame a long view to plants visually captured in a courtyard, this greenery occupying the same space of gaze as the Georg Kolbe female nude sculpture does in the Spanish pavilion. Here, Stinner is re-stating her point about the embedded referentiality of modernism—those spatial fractals again.

Is Stinner’s visual equation—plant show pavilion = high modernist pavilion—such an outrageous one? The Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany is likely the most prestigious recurring event in the art world. Few realize that this massive exhibition is the direct outgrowth of an annual flower show that the German city initiated in the dark years after WWII. In the mid-1950s a small art exhibition was started to complement the

annual showing of floral displays and collections of exotic shrubs. While the art exhibition has since grown to over-take the entire city, the garden show continues, much to the delight of Kasselers, and truth be known, to conceptually-overdrawn and visually- tapped-out art pilgrims, too.

Platform for Palimpsests

The palimpsest was the pre-modern tradition of the re-use of vellum or parchment sheets, where texts or images were scraped off in order to re-use them for new texts or images. A ghost-like layering of images and information called “palimpsest” is the evocative result, as no removal is ever absolute, and information lives on in spectral forms.

The idea of the palimpsest is crucial to many of the works in the Platform Gallery exhibition. The idea is most evident in two images from Stinner’s hometown. Winnipeg (plant) shows two darkened patches on an office’s walnut interior, one a spot where a desk had long been placed, a second where a painting once was hung (or paintings, as there are over-lapping rectangles of different sizes.) In an action analogous to photographic printing itself, these objects protected the walnut panels from degradation from the ultra-violet rays of the sun, the original dark hues of the walnut preserved while the rest of the wall had been blanched by prairie light over the decades. In this Miesian modernist office landscape undergoing renovation or demolition, this visual residue of the effect of objects placed against a photo-sensitive plane makes for a kind of found photogram, Man Ray gone Manitoba.

Winnipeg (coil) is also a palimpsest image, though perhaps not a photogram. It shows a coil of blue computer cable lying on a differentially-stained carpet. The differing tones here document high and low traffic areas marked through the residue of dirt-bearing shoes. Looking carefully, another layer of information is also evident, because some of the most worn-out carpet tiles have been replaced with whiter new ones, adding a checkerboard patterning to the mix. Or perhaps those ghost images come from the effects of sunlight—just as for the previous image—with the shadows of desks and filing cabinets past projected onto the carpet tiles beneath them.

More subtle palimpsests of the effects of light alone—the patterns of shadows cast upon floors and ground planes by illumination sources—are evident in three other images: Minneapolis (doorway), Chicago (tree) and Weyburn (wall). The word “palimpsest” is also used by architects and preservationists, being the residual visual evidence of previous buildings or internal conditions. Winnipeg (generator) is an architectural palimpsest, the markings on a concrete block wall giving evidence of leaks in a wall through differential staining. The grass is greener around the micro-climate of the building, a co-incidence of architectural and landscape types of palimpsest.

The critical term that Stinner herself sometimes uses for these images is “diorama,” those carefully illusionistic museum installations that render a photographic images into three dimensions, or conversely, make a group of physical objects take on the qualities of a flat photograph. Stinner’s interest is in the diorama as an analogue for the mission of

photography itself, and grew with repeated visits to see such displays at the Field Museum of Natural History, across Grant Park from where she completed her graduate studies in photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Stinner speaks of the rare opportunity students there had to work daily with one of the world’s great art collections, and in her case, to come to understand photography through direct access to prints, rather than inter-mediated through publications, slides or digital imagery. She also credits her ongoing passion for all things architectural to her time in the city which more than any other, was the birthplace of the Modern Movement.

More typical of her generation of artists trained under the sign of postmodernism, Stinner soon came to doubt claims to authenticity in any art-form, photography most of all. This veteran of museum studies and museums has a Winnipeg directness in her view of this: “You can’t trust the document,” she said, over the course of a studio tour and discussion of her work and the impact of digital technologies. The sentence which followed that one makes a suitable conclusion—for this essay, and about her remarkable work, past and future: “Because of this, it is a wonderful time for photography.”

-Trevor Boddy, Vancouver, March 7, 2007

Trevor Boddy is a Vancouver art and architectural historian, critic and curator, whose column entitled “Dwelling” appears Fridays at www.globeandmail.com. He authored the first critical monograph on a contemporary Canadian architect, The Architecture of Douglas Cardinal, which was awarded the ‘Alberta Book of the Year’ prize for 1990. Boddy’s writing on buildings and cities has also been awarded the Jack Webster Journalism Prize and the Western Magazine Award. As curator, his Mendel Gallery show Telling Details: The Architecture of Clifford Wiens is the first career retrospective exhibition ever mounted on a living Canadian architect, now touring nationally. His art criticism has appeared in Vanguard and Canadian Art Magazines and in catalogues on the work of Jayce Salloum and Alison Norlen. The world-wide range of Trevor Boddy’s critical writing, teaching and lecturing is demonstrated in contributions to two recent books: a chapter on the state of architectural criticism published by the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, and a chapter on design and urbanism since 9-11 in a book edited by Michael Sorkin for Routledge of London.